Wednesday, February 25, 2015

How Portugal Brilliantly Ended its War on Drugs

February 24th 2015 by Mark Provost @ attn:

In the 1990s, Portugal was faced with a drug epidemic. General drug use wasn’t any worse than neighboring countries, but rates of problematic drug use were off the charts. A 2001 survey found that 0.7 percent of its population had used heroin at least one time, the second highest rate after England and Wales in Europe. So, in 1998, Portugal appointed a special commission of doctors, lawyers, psychologists, and activists to assess the problem and propose policy recommendations. Following eight months of analysis, the commission advised the government to embark on a radically different approach.

Rather than respond as many governments have, with zero-tolerance legislation and an emphasis on law enforcement, the commission suggested the decriminalization of all drugs, coupled with a focus on prevention, education, and harm-reduction. The objective of the new policy was to reintegrate the addict back into the community, rather than isolate them in prisons, the common approach by many governments. Two years later, Portugal’s government passed the commission’s recommendations into law.

Just as important as the specific policies recommended by the commission is an entirely different philosophy. Rather than treating addiction as a crime, it’s treated as a medical condition. João Goulão, Portugal’s top drug official, emphasizes that the goal of the new policy is to fight the disease, not the patients.

Decriminalization doesn’t mean legalization.

Legalization removes all criminal penalties for producing, selling, and possessing drugs whereas decriminalization eliminates jail time for drug users, but dealers are still criminally prosecuted. Roughly 25 countries have removed criminal penalties for the possession of small amounts of certain or all drugs. No country has attempted full legalization.

When Portuguese authorities find someone in possession of drugs, the drug user will eventually go before a three-member, administrative panel that includes a lawyer, a doctor, and a psychologist. In dealing with the drug user, the panel has only three choices: prescribe treatment, fine the user, or do nothing.

Portugal also invested heavily in widespread prevention and education efforts, as well as building rehabilitation programs, needle exchanges, and hospitals.

How did it work?

Levels of drug consumption in Portugal are now among the lowest in the European Union. No surprise, the decriminalization of low-level drug possession has also resulted in a dramatic decline in drug arrests, from more than 14,000 per year to roughly 6,000 once the new policies were implemented. The percentage of drug-related offenders in Portuguese prisons decreased as well -- from 44 percent in 1999 to under 21 percent in 2012.

HIV infection is an area where the results are clear. Before the law, more than half of Portugal's HIV-infected residents were drug addicts. Each year brought 3,000 new diagnoses of HIV among addicts. Today, addicts consist of only 20 percent of HIV-infected patients.

Portugal’s drug control officials and independent studies caution against crediting Portugal's decriminalization as much as its prevention and rehabilitation efforts.

Prospects for ending the U.S. Drug War.

Drug policy in the United States could not be more different. In the U.S., law enforcement still takes center stage, and the war on drugs is defended by vested interests -- from police unions to private prison companies -- that command billions in resources. While the top drug control official in Portugal is a doctor, the U.S. has a drug czar who specializes in law enforcement.

But advocates hoping to change the system have something they don’t: scientific evidence and popular support.

In early 2014, the U.K.'s government conducted an eight-month study comparing drug laws and rates of drug use in 11 countries, including Portugal. Published in October, the report concludes that “we did not in our fact-finding observe any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country.” It was the U.K.’s first official recognition that its war on drugs has been a complete failure since Parliament passed the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act.

Another sign of hope is the near universal view among Americans that the drug war is not working. A Pew poll from April 2014 revealed that two out of three Americans think people shouldn’t be prosecuted for drug possession. Sixty-three percent support eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, and 54 percent support full marijuana legalization. States have made more progress changing drug laws than the federal government, particularly when the decision is left to voters, who have passed recreational marijuana legalization or medical marijuana legalization by referenda in several states.

In the 1990s, Portugal was faced with a drug epidemic. General drug use wasn’t any worse than neighboring countries, but rates of problematic drug use were off the charts. A 2001 survey found that 0.7 percent of its population had used heroin at least one time, the second highest rate after England and Wales in Europe. So, in 1998, Portugal appointed a special commission of doctors, lawyers, psychologists, and activists to assess the problem and propose policy recommendations. Following eight months of analysis, the commission advised the government to embark on a radically different approach.

Rather than respond as many governments have, with zero-tolerance legislation and an emphasis on law enforcement, the commission suggested the decriminalization of all drugs, coupled with a focus on prevention, education, and harm-reduction. The objective of the new policy was to reintegrate the addict back into the community, rather than isolate them in prisons, the common approach by many governments. Two years later, Portugal’s government passed the commission’s recommendations into law.

Just as important as the specific policies recommended by the commission is an entirely different philosophy. Rather than treating addiction as a crime, it’s treated as a medical condition. João Goulão, Portugal’s top drug official, emphasizes that the goal of the new policy is to fight the disease, not the patients.

Decriminalization doesn’t mean legalization.

Legalization removes all criminal penalties for producing, selling, and possessing drugs whereas decriminalization eliminates jail time for drug users, but dealers are still criminally prosecuted. Roughly 25 countries have removed criminal penalties for the possession of small amounts of certain or all drugs. No country has attempted full legalization.

When Portuguese authorities find someone in possession of drugs, the drug user will eventually go before a three-member, administrative panel that includes a lawyer, a doctor, and a psychologist. In dealing with the drug user, the panel has only three choices: prescribe treatment, fine the user, or do nothing.

Portugal also invested heavily in widespread prevention and education efforts, as well as building rehabilitation programs, needle exchanges, and hospitals.

How did it work?

Levels of drug consumption in Portugal are now among the lowest in the European Union. No surprise, the decriminalization of low-level drug possession has also resulted in a dramatic decline in drug arrests, from more than 14,000 per year to roughly 6,000 once the new policies were implemented. The percentage of drug-related offenders in Portuguese prisons decreased as well -- from 44 percent in 1999 to under 21 percent in 2012.

HIV infection is an area where the results are clear. Before the law, more than half of Portugal's HIV-infected residents were drug addicts. Each year brought 3,000 new diagnoses of HIV among addicts. Today, addicts consist of only 20 percent of HIV-infected patients.

Portugal’s drug control officials and independent studies caution against crediting Portugal's decriminalization as much as its prevention and rehabilitation efforts.

Prospects for ending the U.S. Drug War.

Drug policy in the United States could not be more different. In the U.S., law enforcement still takes center stage, and the war on drugs is defended by vested interests -- from police unions to private prison companies -- that command billions in resources. While the top drug control official in Portugal is a doctor, the U.S. has a drug czar who specializes in law enforcement.

But advocates hoping to change the system have something they don’t: scientific evidence and popular support.

In early 2014, the U.K.'s government conducted an eight-month study comparing drug laws and rates of drug use in 11 countries, including Portugal. Published in October, the report concludes that “we did not in our fact-finding observe any obvious relationship between the toughness of a country’s enforcement against drug possession, and levels of drug use in that country.” It was the U.K.’s first official recognition that its war on drugs has been a complete failure since Parliament passed the 1971 Misuse of Drugs Act.

Another sign of hope is the near universal view among Americans that the drug war is not working. A Pew poll from April 2014 revealed that two out of three Americans think people shouldn’t be prosecuted for drug possession. Sixty-three percent support eliminating mandatory minimum sentencing, and 54 percent support full marijuana legalization. States have made more progress changing drug laws than the federal government, particularly when the decision is left to voters, who have passed recreational marijuana legalization or medical marijuana legalization by referenda in several states.

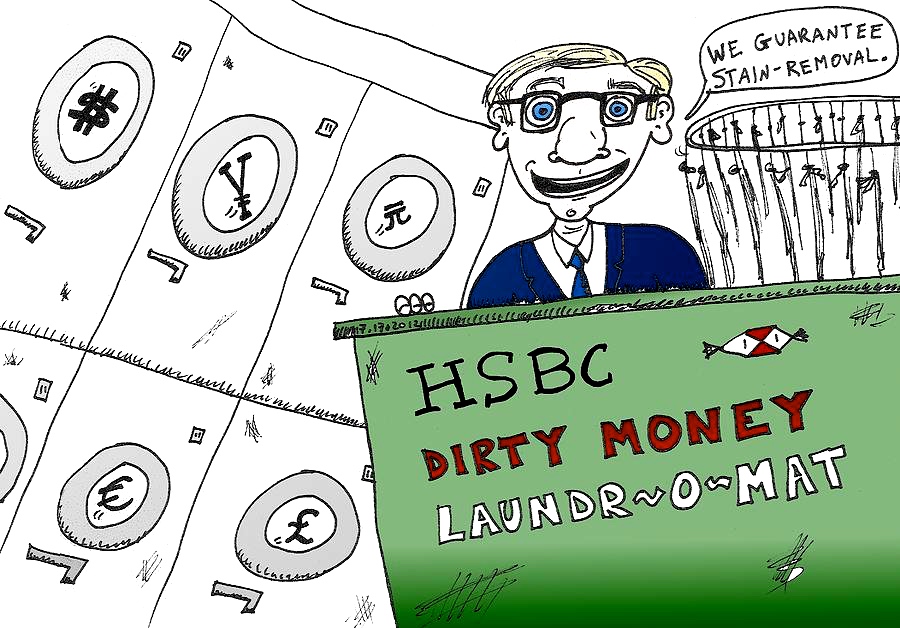

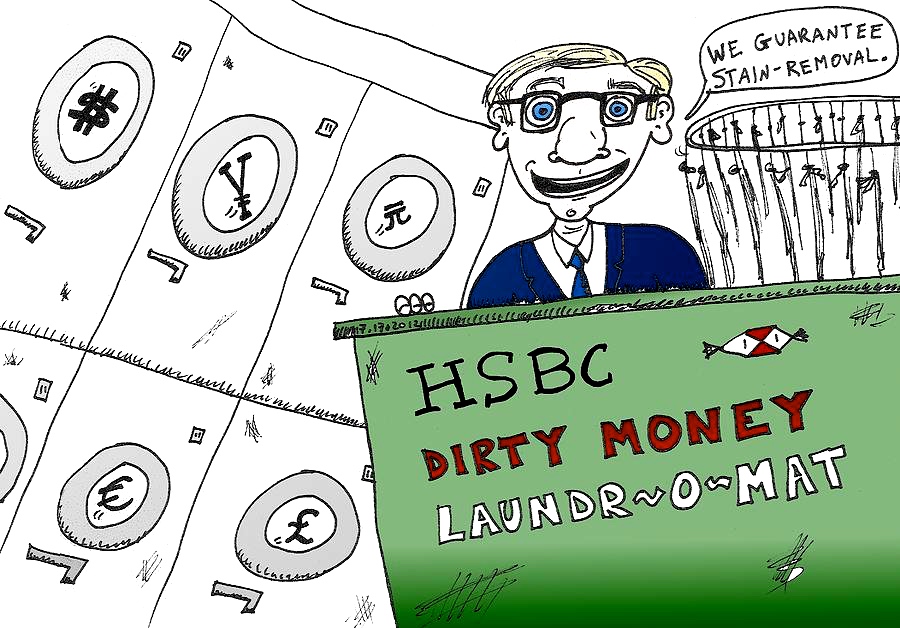

HSBC Bank Scandal Widens As Collusion With U.K. Government and Media Is Exposed

Mon, 2/23/2015 - by Charlotte Dingle

SBC, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation headquartered in the UK, is in fresh trouble. As John Christensen, director of the Tax Justice Network and a leading authority on tax evasion, put it: “An ordinary individual caught doing what HSBC was doing would have all of their assets taken away and would go to prison.”

The week before last it came out that the company's Swiss arm was allowing wealthy customers, allegedly including drug and arms dealers, to dodge tax and hide millions of dollars in offshore accounts. Swiss, Belgian and French authorities are investigating the bank, but the UK government almost immediately refused to launch an in-depth probe.

Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne was criticized for laying conspicuously low after the international story broke. He finally appeared more than a week later, telling an audience at the Tate Gallery on London's South Bank that it was a matter for the “prosecuting authorities.”

“I don’t think it would be right for [me] to direct prosecutions against individuals or individual companies,” Osborne said.

Last Wednesday, Peter Oborne, the chief political commentator for the UK's leading conservative broadsheet, the Daily Telegraph, resigned over the paper's biased coverage of the case. By Friday, it became clear that the newspaper wasn't only attempting to retain its advertising revenue from the bank – but that its owners had recently received a £250 million loan from HSBC.

Oborne has called for an independent enquiry following an editorial the paper published claiming “no apology” for its actions. For now, the tale of high-level government and media collusion involving a deeply corrupt financial institution continues.

This Monday, HSBC is set to “apologize” for its actions when it releases its full-year figures for 2014. It's not the first time the bank has been in hot water over what it's doing with its clients' money. In 2012, the bank was forced to pay out $1.9 billion following allegations that it assisted Mexican drug traffickers moving their money around the financial system. A total of $881 million was laundered across HSBC bank accounts. Yet the bank was allowed to continue trading.

“HSBC has been very closely politically connected to the British government for many decades,” John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network told Occupy.com. “Right back to the opium wars, when the big British trading houses were trading opium out of India into China and the Royal Navy was used to break open the Chinese market.

"More recently, the British government was very active pushing in Washington for HSBC not to lose its license in the U.S. over the Mexican drug money scandal," he added, and "it's more than the British government being ineffective in punishing HSBC – it has a long history in being very active protecting HSBC from investigation. It is a complete dereliction of the government's duty that it refuses to look into this situation.”

But the scandal goes even further than that, Christensen said.

“We know HSBC has been involved in criminal activity, at many levels. And it's not just collusion with tax evasion and the marketing of tax evasion services to clients through their Geneva branch, not just the drug money laundering in the U.S.," he continued. "It's also their involvement with the rigging of the Libor (London Interbank offered rate) market, interest rate settlements and currency market exchanges. So they've been involved in rigging markets, avoiding drug money, laundering, and the list just goes on and on.”

So how does he feel about the Daily Telegraph being in cahoots with the bank?

“We are in a terrible situation in this country and the Telegraph isn't unique in this,” Christensen sad. “So many news and media outlets are dependent on advertising, and the financial services industry is a major source of advertising revenue. We're now in a position where we can no longer be sure that our media will be prepared to run stories like this because they're scared of losing advertising revenue. And when financial matters are commented upon, it tends to involve voices from the City of London financial circles – bringing all sorts of conflicts of interest. So we have the worst of both worlds: we have a media scared of losing its revenue which relies very heavily on these conflicted voices.”

Christensen said he's frightened that a lack of sanctions against HSBC would set the precedent for other banks and large corporations to relax their rules.

“There should be a thorough independent inquiry and the company directors should be called to account and sent to prison. The government should send out a strong message that behavior like this won't be tolerated within the company," he concluded. But, "what will actually happen is that they won't be sent to prison, and the message will go out to other banks and to the general public that banks can engage in criminal behavior with impunity because the British government will do nothing.”

SBC, the Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation headquartered in the UK, is in fresh trouble. As John Christensen, director of the Tax Justice Network and a leading authority on tax evasion, put it: “An ordinary individual caught doing what HSBC was doing would have all of their assets taken away and would go to prison.”

The week before last it came out that the company's Swiss arm was allowing wealthy customers, allegedly including drug and arms dealers, to dodge tax and hide millions of dollars in offshore accounts. Swiss, Belgian and French authorities are investigating the bank, but the UK government almost immediately refused to launch an in-depth probe.

Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne was criticized for laying conspicuously low after the international story broke. He finally appeared more than a week later, telling an audience at the Tate Gallery on London's South Bank that it was a matter for the “prosecuting authorities.”

“I don’t think it would be right for [me] to direct prosecutions against individuals or individual companies,” Osborne said.

Last Wednesday, Peter Oborne, the chief political commentator for the UK's leading conservative broadsheet, the Daily Telegraph, resigned over the paper's biased coverage of the case. By Friday, it became clear that the newspaper wasn't only attempting to retain its advertising revenue from the bank – but that its owners had recently received a £250 million loan from HSBC.

Oborne has called for an independent enquiry following an editorial the paper published claiming “no apology” for its actions. For now, the tale of high-level government and media collusion involving a deeply corrupt financial institution continues.

This Monday, HSBC is set to “apologize” for its actions when it releases its full-year figures for 2014. It's not the first time the bank has been in hot water over what it's doing with its clients' money. In 2012, the bank was forced to pay out $1.9 billion following allegations that it assisted Mexican drug traffickers moving their money around the financial system. A total of $881 million was laundered across HSBC bank accounts. Yet the bank was allowed to continue trading.

“HSBC has been very closely politically connected to the British government for many decades,” John Christensen of the Tax Justice Network told Occupy.com. “Right back to the opium wars, when the big British trading houses were trading opium out of India into China and the Royal Navy was used to break open the Chinese market.

"More recently, the British government was very active pushing in Washington for HSBC not to lose its license in the U.S. over the Mexican drug money scandal," he added, and "it's more than the British government being ineffective in punishing HSBC – it has a long history in being very active protecting HSBC from investigation. It is a complete dereliction of the government's duty that it refuses to look into this situation.”

But the scandal goes even further than that, Christensen said.

“We know HSBC has been involved in criminal activity, at many levels. And it's not just collusion with tax evasion and the marketing of tax evasion services to clients through their Geneva branch, not just the drug money laundering in the U.S.," he continued. "It's also their involvement with the rigging of the Libor (London Interbank offered rate) market, interest rate settlements and currency market exchanges. So they've been involved in rigging markets, avoiding drug money, laundering, and the list just goes on and on.”

So how does he feel about the Daily Telegraph being in cahoots with the bank?

“We are in a terrible situation in this country and the Telegraph isn't unique in this,” Christensen sad. “So many news and media outlets are dependent on advertising, and the financial services industry is a major source of advertising revenue. We're now in a position where we can no longer be sure that our media will be prepared to run stories like this because they're scared of losing advertising revenue. And when financial matters are commented upon, it tends to involve voices from the City of London financial circles – bringing all sorts of conflicts of interest. So we have the worst of both worlds: we have a media scared of losing its revenue which relies very heavily on these conflicted voices.”

Christensen said he's frightened that a lack of sanctions against HSBC would set the precedent for other banks and large corporations to relax their rules.

“There should be a thorough independent inquiry and the company directors should be called to account and sent to prison. The government should send out a strong message that behavior like this won't be tolerated within the company," he concluded. But, "what will actually happen is that they won't be sent to prison, and the message will go out to other banks and to the general public that banks can engage in criminal behavior with impunity because the British government will do nothing.”